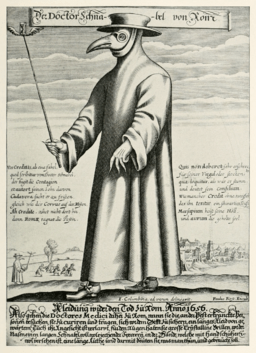

Copper engraving 1656, Paul Furst

(public domain)

As the world shutters its doors, and people every where practice ‘social distancing’ in a desperate attempt to slow the spread of COVID-19, it might be useful to look back at past pandemics, especially the plague.

Bubonic plague ravaged the world many times, though perhaps the most well-known is the Black Death, (1347-1351), one of the worst pandemics humans have ever known. This outbreak probably started in Central Asia and was carried both east and west by traders. Estimates of deaths vary from one quarter to one third of the population of Europe. Between 75 and 200 million people throughout Eurasia died. No one understood what caused the disease, how to prevent it, or how to treat it. It spread rapidly, halting business and trade, and ultimately changing society.

In reality the plague is caused by bacteria transmitted to humans through rat fleas or from the coughing and sneezing of an infected person. No one knew about bacteria during the Black Death, so there were many false beliefs on what caused the illness. Some people thought it was a sign of God’s wrath against sinners and a generally wicked population. Others thought it was caused by evil spirits who pricked victims with poisoned lances. Some thought you could get sick merely by looking at the sick. They believed the infection was carried from the eyes of the sick to the eyes of the healthy. Scared villagers blamed cats, dogs, Jews, or migrants as carriers.

Some people looked for more ‘scientific’ explanations. Many believed the infection was spread by the air itself, or from poisonous fumes coming from underground. Others maintained it was due to a thick, stinking mist blown over Italy from the east. At least one physician attributed the illness to the movements of the planets. No one seemed to think the ubiquitous rats and fleas caused it.

Since no one knew what caused the disease, means of preventing it were widely varied and mostly ineffective. In the Middle Ages, health or lack thereof was seen as a function of the four humours of the body: blood, black bile, phlegm and yellow bile. Following the theory of humours, the Paris medical faculty advised against eating cold, moist, watery foods or exercising too much. If it rained, they advised taking a dose of fine treacle (a thick syrup like molasses). They also suggested fat people should not sit in the sunshine.

In the face of this largely useless advice, many folk remedies developed. Perhaps carrying a bunch of flowers, especially lavender, could freshen or purge the bad air. Smoke was also seen as a disinfectant. Cunning advertisers tried to sell special powders to burn. Vinegar was used as a sanitizer. In London markets, coins were dropped in a bowl of vinegar before changing hands. Magic charms were used to ward off the plague. The word ‘abracadabra’ could be written in an inverted triangle, leaving off the first letter in each new line. As the word shrank away, so too would the disease.

Most of these efforts had little effect and more desperate measures set in. The medieval version of ‘social distancing’ meant plague victims might be shunned by family and friends and left to die alone. Public assemblies became illegal. Some households closed themselves up with extra stocks of food and water, hoping to wait out the disease. Others fled, unwittingly carrying the deadly bacteria with them. In many places, infected houses were quarantined by the authorities with all the inhabitants inside. This was different from voluntary isolation because these people rarely had the opportunity or money to buy extra supplies. When the sick were confined with the healthy, nearly everyone died.

Some doctors fled, but many tried to help their patients. They tried bleeding, lancing the swellings, or tying a toad or a live, plucked chicken to the swellings. Victims surviving the illness sometimes died from the cure.

Doctors today have a lot better idea of how to treat illness and a much better understanding of the spread of disease. But people in general have not changed much. Granted, COVID-19 is nowhere near as deadly as the bubonic plague, but it is new and unknown. People today self-isolate or ‘shelter in place’ after stocking up on toilet paper, flour, and canned goods. Borders are closed and migrants are viewed with suspicion. No one knows how long this will last.

The bubonic plague re-shaped medieval society in many ways, especially economically. With so many people dead, worker shortages eventually led to improved conditions for workers. None of us today have lived through such horror like the plague. But our own pandemic has already had far-reaching effects. COVID-19 has shuttered businesses world-wide, closed schools and restaurants, and cancelled weddings and funerals. Time will tell what permanent changes this disease will have on our own society.

The caption, translated, says: “The costume of doctors and other people who visit those infected with the plague. It is made of levant Morocco (sheep, goat, or seal leather), the mask has crystal eyes and a long nose that is stuffed full of perfumes.”

(This protective gear was not used during the Black Death, but during later epidemics.)

(Note: Large portions of this posting come from my article “The Plague in the Middle Ages,” in Tournaments Illuminated, Summer 1983, published under my SCA name, Taira d’en Farraige Thiar.)