Examining the Legend

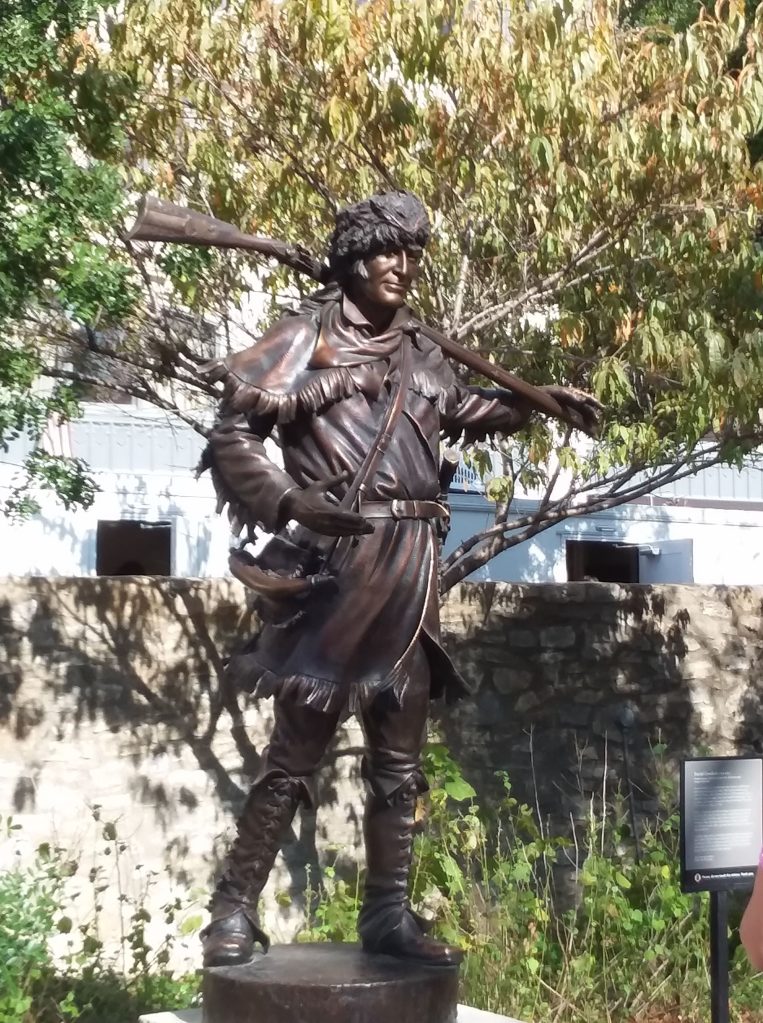

As a child I idolized Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone, especially as portrayed by Fess Parker on television and transformed into legend by American Frontier lore and tall tales.

In my mind, they lived at the same time (the ‘old days’) Both wore coonskin caps, alternately fought and befriended Indians, and lived on the wild frontier (which I thought was somewhere vaguely west). In reality, Boone (1734-1820) was born almost fifty years before Crocket (1786-1836) and died sixteen years earlier. Both were politicians as well as frontiersmen. Daniel Boone fought in the Revolutionary War, and lived to tell the tales. Davy Crockett fought in the Texas War for Independence, and died at the Alamo.

Back then, Crockett’s death always struck me as particularly tragic– a young adventurer struck down in his prime. I read of his exploits as a legendary hero, killed fighting for liberty. It was romantic (in the Byronic sense). And because of my interest (obsession?) with Davy Crockett, I became fascinated by the stories of the Alamo, the site of the most famous battle for Texan independence. I read of the heroic stand made by a handful of American heroes who all died protecting Texas from the cruel Mexican army invaders. Like Crocket’s own larger-than life tale, the stories I heard of the Alamo stretch the truth into more legend than fact.

I had an opportunity in December to visit the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. On a warm sunny day, I stood in line with a couple hundred people for a timed entrance ticket. The place was crowded, in spite of Covid-19 restrictions limiting access. As I wandered through the well-laid out exhibit hall, the shaded gardens, and the white, limestone church, I learned more of the true history of the place.

What is now known as the Alamo was built in 1744-1758, as a Spanish mission (Mision San Antonio de Valero) with the purpose of ‘educating’ (converting) the Indians. Much of the building collapsed before it was finished.Still, it was used as a mission and church until 1793, when it was abandoned. In 1803, ten years later, the compound became a fortress which came to be known as the Alamo, meaning ‘cottonwood’ in Spanish. This fairly small, fairly obscure, place gained its fame from the battle fought there in 1836.

The early 1800’s were a time of great upheaval for Mexico, which included Texas at that time. Mexico’s war to separate from Spain lasted for years, with Spain only recognizing Mexico’s independence in 1836. Because of the riches in Mexico (ie silver), the opportunities for trade and good lands, many Anglo-Americans moved out of the United States and into Texas during this period.

Mexico’s government grew less and less tolerant of these Anglo immigrants (called Texians). Texians, in turn, chafed under Mexican rule. One among many grievances was that Mexico had abolished slavery in 1830. The Texians did not want to give up their ‘property’. Throughout 1835, the Texians, along with many volunteers from the United States, and some ‘Tejanos’ (Mexican citizens of Texas), defeated several small Mexican garrisons in Texas. But the resulting government was disorganized and ineffective. General Santa Ana vowed to defeat these rebels once and for all. With a huge army, Santa Ana met the Texian contingent at the Alamo and defeated them, killing nearly all of the Alamo defenders. (The women, children, some Mexican citizens, and slaves were released. Survivors who surrendered were executed.)

This battle served to rally the Texian Army, and they went on to soundly defeat Santa Ana. The winners declared the land was now independent, the Republic of Texas. However, Mexico, enraged at what they saw as U.S. interference in their land, refused to recognize the Republic of Texas. The U.S. annexation of Texas as the 28th state in 1845 led to the Mexican-America War.

In spite of the legends proclaiming their heroism, the defenders of the Alamo could be considered an immigrant take-over of Mexican land, not the heroic last stand of a people fighting invaders. History is often the stories told by the winners. In this case, although the Texians lost at the Alamo, they later won the war, giving them the power to reshape the telling to their advantage. The story of the Alamo should probably be taken as a cautionary tale: legends can lie.