Seafood two thousand miles from the ocean? No problem. Fresh strawberries in the middle of a February snowstorm? Why not? In the modern world of well-stocked grocery stores, world-wide distribution, and a multiplicity of preservation options, we can generally eat whatever we want whenever we want. This hasn’t always been true. For centuries our ancestors relied on highly nutritious root vegetables to get through the winter. Stored in cool, dark cellars, root vegetables keep well for many months. While we still enjoy many root vegetables, like carrots and potatoes, others have become less popular. This week’s recipe focuses on two such vegetables: the parsnip and the skirret.

Seafood two thousand miles from the ocean? No problem. Fresh strawberries in the middle of a February snowstorm? Why not? In the modern world of well-stocked grocery stores, world-wide distribution, and a multiplicity of preservation options, we can generally eat whatever we want whenever we want. This hasn’t always been true. For centuries our ancestors relied on highly nutritious root vegetables to get through the winter. Stored in cool, dark cellars, root vegetables keep well for many months. While we still enjoy many root vegetables, like carrots and potatoes, others have become less popular. This week’s recipe focuses on two such vegetables: the parsnip and the skirret.

The parsnip has an unusual history. Even the name is a bit odd. The word comes from the Latin ‘pastinum’ (fork) through Old French ‘pasnaie’. Parsnips are native to Eurasia, but have spread world-wide. In fact, parsnip’s wild cousin is a dangerous invasive posing problems for hikers. The stems and leaves contain a toxic sap that can cause a bad rash when damp skin that has come in contact with the plant is exposed to sunlight. Cultivated parsnips are harvested the first year of growth, so they are not allowed to develop the tall stems and leaves that cause the problem.

The parsnip has an unusual history. Even the name is a bit odd. The word comes from the Latin ‘pastinum’ (fork) through Old French ‘pasnaie’. Parsnips are native to Eurasia, but have spread world-wide. In fact, parsnip’s wild cousin is a dangerous invasive posing problems for hikers. The stems and leaves contain a toxic sap that can cause a bad rash when damp skin that has come in contact with the plant is exposed to sunlight. Cultivated parsnips are harvested the first year of growth, so they are not allowed to develop the tall stems and leaves that cause the problem.

Parsnips were cultivated by the Romans, who sometimes confused them with carrots. (Parsnips are indeed related to carrots, as well as parsley. In Roman times, carrots were purple or white, hence the confusion.) The Romans held that parsnips were an aphrodisiac. Emperor Tiberius even accepted parsnips as payment for part of the tribute due from German tribes.

Parsnips can be left in the ground for storage (except in areas where the ground freezes solid) and are sweeter after winter frosts. They were used as a sweetener in Europe before cane or beet sugar was discovered. Both French and British colonists introduced parsnips to the Americas, where the root was popular in cookery for decades. (Potatoes eventually replaced the parsnip as the most popular root vegetable.)

Valued as a staple in Europe and the Americas, lauded as a sweetener for many centuries, and prized for medicinal purposes in China, the parsnip is now fed to the pigs as often as it is eaten by humans.

Parsnip’s cousin, the skirret is another misunderstood root vegetable that has lost popularity. In fact, it is difficult to even find skirrets today. Also know as a crummock, or water parsnip, the skirret is fairly low yield, so it is rarely grown commerically. Later cooks have sometimes confused the skirret with carrots, though they are not the same. In German, the skirret is called zuckerwürzel (sugar root). By medieval times, the name had morphed into ‘skyrwates’, with the folk etymology of ‘pure whites’. Like the parsnip, skirrets came out of Asia, and were used in Europe by Roman times.

In medieval times, skirrets were considered mostly beneficial. The Benedictine Abbess/ Herbalist Hildegard von Bingen recommended they be used in moderation, as too much could cause a fever or intestinal troubles. She also suggested mashed skirrets mixed with oil made a good poultice for weak skin on the face. In Maud Grieve’s 16th century book, a Modern Herbal, skirrets are recommended for chest complaints. Skirrets remained popular at least until the 17th century, when Nicholas Culpeper recognized them as nourishing, but cautioned they could cause ‘wind’ and provoke venery and urine.

Despite my earlier claim that it is now mostly possible to what we want when we want, I could not find skirrets in any local grocery store. So the following recipe relies only on parsnips for a delicious side dish to any meal.

Parsnip Pie

To make a tart of parsneps & skirrits

Seethe yr roots in water & wine, then pill them & beat them in a morter with raw eggs and grated bread. Bedew them often with rose water & wine, then streyne them & put suger to them & some juice of leamons, & put it into yr crust; & when yr tart is baked, cut it up & butter it hot, or you may put some butter into it when you set it in yr oven & and eat it cold. (Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery, 97)

My version:

Pie crust dough for 1 pie, top and bottom 4 c. mashed parsnips 4 eggs 1 c. wine sweet white wine Juice of 1 lemon (¼ c.) ¼ c. sugar ¼ c. bread crumbs 2 T. rose water ¼ c. butter (melted) Roll out half of the pie crust dough andplace in a deep 10” pie pan. Prick all over (bottom and sides) with a fork. Bake for 10 minutes, 425 degrees. Meanwhile, peel the parsnips and cut them into chunks. Boil until tender. Cool slightly and mash. Mix mashed parsnips with the remainder of the ingredients. Fill the pie. Roll out the top crust and cover the pie. Pinch it closed. (Brush the edge of the bottom crust with water to help seal the edge.) Cut vents in the top crust. Bake at 350 degrees until top crust is golden (about 1 hour). Serve warm or cold This pie is very good, barely sweet, making a good side dish for a meal. For a dessert or breakfast pie, add up to ½ c. additional sugar.

References:

Culpeper, Nicholas. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal and English Physician. 1653. (Applewood Books reprint)

Grieve, Maud. A Modern Herbal. botanical.com (retrieved 4/3/2019)

Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery. Edited by Karen Hess

Martinko, Katherine. Meet the Skirret, the long-forgotten Tudor vegetable. Treehugger.com. 3/11/2016

The Parsnip. Towne’s Harvest Garden. Montana State. University. (pdf, retrieved 4/3/2019)

Though the night when “visions of sugar plums danced” has passed, Christmas candy is still plentiful in my house. Christmas is a time of celebration, and celebration most often brings sweet treats. A little investigation shows that traditions of candy go way back.

Though the night when “visions of sugar plums danced” has passed, Christmas candy is still plentiful in my house. Christmas is a time of celebration, and celebration most often brings sweet treats. A little investigation shows that traditions of candy go way back.

Ask a dozen people about mincemeat and you’ll like get one of two answers. Some will fondly remember how their mother or grandmother made mincemeat pies. Most of the rest will say, “Huh? What’s in that anyway? Does it really have meat in it?”

Ask a dozen people about mincemeat and you’ll like get one of two answers. Some will fondly remember how their mother or grandmother made mincemeat pies. Most of the rest will say, “Huh? What’s in that anyway? Does it really have meat in it?”

September is the harvest month–the time to gather the abundant bounty from our summer gardens . And nothing demonstrates abundance quite so well as zucchini squash. It’s so easy to grow that even a complete amateur gardener can produce more zucchini than any family can reasonably eat in one season. Zucchini grows well in almost any soil, survives drought and neglect and even produces when choked by weeds left by the lazy gardener. But zucchini is a relative newcomer to the panoply of summer squashes. It is a hybrid variety of Cucurbita pepo (all summer squashes belong to this family), developed in Italy in the second half of the 19th century. The first records of zucchini in America are not quite a hundred years old, dating from the 1920’s.

September is the harvest month–the time to gather the abundant bounty from our summer gardens . And nothing demonstrates abundance quite so well as zucchini squash. It’s so easy to grow that even a complete amateur gardener can produce more zucchini than any family can reasonably eat in one season. Zucchini grows well in almost any soil, survives drought and neglect and even produces when choked by weeds left by the lazy gardener. But zucchini is a relative newcomer to the panoply of summer squashes. It is a hybrid variety of Cucurbita pepo (all summer squashes belong to this family), developed in Italy in the second half of the 19th century. The first records of zucchini in America are not quite a hundred years old, dating from the 1920’s. This original recipe calls for peeling the pattypan squash. I found that it is very difficult to peel because of the irregular shape. In the days of modern appliances, peeling the squash is unnecessary. Placing the boiled, unpeeled squash in a food processor and processing it for 2 minutes produces a sauce just as smooth as the colonial method of forcing the cooked squash through a colander.

This original recipe calls for peeling the pattypan squash. I found that it is very difficult to peel because of the irregular shape. In the days of modern appliances, peeling the squash is unnecessary. Placing the boiled, unpeeled squash in a food processor and processing it for 2 minutes produces a sauce just as smooth as the colonial method of forcing the cooked squash through a colander.

There are a number of challenges in following this recipe. First I had to figure out what it means to raise the crust. A raised crust is not, as I first thought, made from a yeast dough. Rather, a raised crust is a thicker crust made without a mold. So raising the crust means pushing the sides up to make a free-standing, pie-shaped bowl, often in a rectangular shape.

There are a number of challenges in following this recipe. First I had to figure out what it means to raise the crust. A raised crust is not, as I first thought, made from a yeast dough. Rather, a raised crust is a thicker crust made without a mold. So raising the crust means pushing the sides up to make a free-standing, pie-shaped bowl, often in a rectangular shape.  P.S. Whoever invented the phrase ‘easy as pie,’ probably never made a scratch pie.

P.S. Whoever invented the phrase ‘easy as pie,’ probably never made a scratch pie. Sometime in the middle of the eighteenth century, an adventurous (or careless) housewife added pearlash to her dough and the first chemical leavening was discovered. Before pearlash found its way into food, housewives had to use yeast or egg whites if they wanted their baked goods to rise. But it takes a long time to whip egg whites to a froth, and the resulting mix is not very stable. Yeast also takes a long time to work. Thus with the new chemical leavener, pearlash, cooks could bake ‘quick’ breads, a great convenience in the labor-intense colonial kitchen.

Sometime in the middle of the eighteenth century, an adventurous (or careless) housewife added pearlash to her dough and the first chemical leavening was discovered. Before pearlash found its way into food, housewives had to use yeast or egg whites if they wanted their baked goods to rise. But it takes a long time to whip egg whites to a froth, and the resulting mix is not very stable. Yeast also takes a long time to work. Thus with the new chemical leavener, pearlash, cooks could bake ‘quick’ breads, a great convenience in the labor-intense colonial kitchen.

Spring is finally here. The ice is off the lake and the trees are budding out. With the end of the sugaring season, it’s time to talk about maple sap. Maple syrup is one of the uniquely American foods. No one knows for sure when the indigenous people of North America began collecting ‘sweet water’ from maples and other native trees, but it was long before Europeans arrived. Sixteenth century French fur traders described how the natives collected sap in birch-bark baskets. When the sap rose in late winter and other food sources were scarce, Indians drank the ‘sweet water’ straight. They also boiled meat or other foods in it. Using hot rocks they boiled it down to make syrup or sugar.They even molded the sugar into decorative shapes. In other words, maple sap was an important part of the native food culture in North America.

Spring is finally here. The ice is off the lake and the trees are budding out. With the end of the sugaring season, it’s time to talk about maple sap. Maple syrup is one of the uniquely American foods. No one knows for sure when the indigenous people of North America began collecting ‘sweet water’ from maples and other native trees, but it was long before Europeans arrived. Sixteenth century French fur traders described how the natives collected sap in birch-bark baskets. When the sap rose in late winter and other food sources were scarce, Indians drank the ‘sweet water’ straight. They also boiled meat or other foods in it. Using hot rocks they boiled it down to make syrup or sugar.They even molded the sugar into decorative shapes. In other words, maple sap was an important part of the native food culture in North America. Hannah Glasse gives similar directions for making maple sugar. She claims ”This sugar if refined by the usual process, may be made into as good single or double refined loaves, as were ever made from the sugar obtained from the juice of the West India cane” (Glasse, 141). She also talks about maple molasses, which is really what we would call maple syrup today.

Hannah Glasse gives similar directions for making maple sugar. She claims ”This sugar if refined by the usual process, may be made into as good single or double refined loaves, as were ever made from the sugar obtained from the juice of the West India cane” (Glasse, 141). She also talks about maple molasses, which is really what we would call maple syrup today. To Make Mush

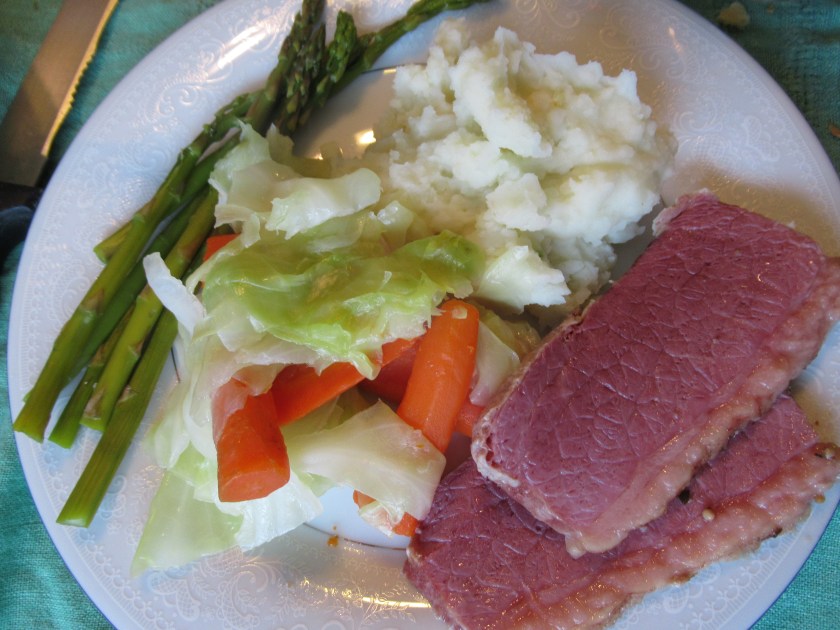

To Make Mush As March draws toward its closing, we have just finished celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the biggest Irish-American holiday of the year, with one of my favorite meals–traditional corned beef and cabbage.

As March draws toward its closing, we have just finished celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the biggest Irish-American holiday of the year, with one of my favorite meals–traditional corned beef and cabbage.