Whether you call them hérisson (Fr.) or igel (German), sündiznó (Hungarian) ,or yrchouns (Middle English), hedgehogs are terribly cute. Of course, they haven’t always been regarded as such. Like guinea pigs and rabbits, this enchanting little creature has been considered a delicacy for the table. In fact, some evidence points to 8000 years ago, when roast hedgehog was served to the rich. In medieval times, the cook was advised to put a reluctant hedgehog in hot water to make it unroll so it could be properly cut open, cleaned and roasted.

That has changed. Perhaps it was because hedgehogs are so prickly, or perhaps it was that the medieval cooks loved subtleties (foods cooked to look like something else, serving also as table decorations). In any case, roasting actual hedgehogs became less popular among the elite, and hedgehog-themed foods took the animal’s place on the table.

My first encounter with a hedgehog subtlety was years ago, cooking for a medieval feast in the Society for Creative Anachronisms. The recipe, called hedgehogs or yrchouns was a sort of glorified meatloaf/meatball stuck all over with almonds.

The original recipe: Yrchouns. Take Piggis mawys, and skalde hem wel; take groundyn Porke, and knede it with Spicerye, with pouder Gyngere, and Salt and Sugre; do it on the mawe, but fille it nowt to fulle; then sewe hem with a fayre threde, and putte hem in a Spete as men don piggys; take blaunchid Almaundys, and kerf hem long, smal, and scharpe, and frye hem in grece and sugre; take a litel prycke, and prykke the yrchons, An putte in the holes the Almaundys, every hole half, and eche fro other; ley hem then to the fyre; when they ben rostid, dore hem sum wyth Whete Flowre, and mylke of Almaundys, sum grene, sum blake with Blode, and lat hem nowt browne to moche, and serue forth (Harleian Manuscript 279, c. 1430)

This recipe seems to be a variation from the French cookbook, Le Viandier de Taillevent. In that recipe, no almond spikes are included. Rather the rounded, stuffed sausage looks like a hedgehog without spines. (Yrchoun is an anglicization of the French hérisson.)

My version:

2 lb. ground meat 2 t. Ginger 1 t. mace 1 t. Salt ½ c. breadcrumbs 1 egg Slivered almonds, raisins, food coloring Mix the first 6 ingredients and form into oval shaped balls. Color some of the almonds red and yellow with food coloring.Stick the almonds into the balls to resemble spines. Add 2 raisins for eyes. Bake 350 degrees about 30 minutes.

Notes: Other recipes for hedgehogs suggest other meats,(ie mutton) which is why I use a mixture of pork and beef. I add breadcrumbs and egg to hold the mixture together more like a meatball, though neither is suggested in the original. (The French recipe calls for soft cheese for binding.) Spicerye just means spices, so which spices are added is up to the cook. I use mace as fairly common medieval spice added to ginger in meats. I leave out the sugar since it really isn’t necessary. Raisin eyes are not documented as period correct, but the French recipe does include raisins in the mixture.

Having enjoyed medieval meatball hedgehogs for years, was recently astounded to see a completely different sort of hedgehog recipe in colonial and early American cookery. In the 1805 version of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, by Hannah Glass, there is a recipe for an almond paste hedgehog (a dish which in my mind is neither plain nor easy if the ‘marzipan’ is done by hand.)

Take two pounds of blanched almonds, beat them well in a mortar, with a little canary and orange-flower water, to keep them from oiling. Make them into stiff paste, then beat in the yolks of twelve eggs, leave out five of the whites, put to it a pint of cream sweetened with sugar, put in a half pound of sweet butter melted, set it on a furnace or slow fire, and keep it constantly stirring, till it is stiff enough to be made in the form of a hedgehog, then stick it full of blanched almonds, slit and stuck up like the bristles of a hedgehog, then put it into a dish; take a pint of cream, and the yolks of four eggs beat up, sweetened with sugar to your palate. Stir them together over a slow fire till it is quite hot; then pour it round the hedgehog in a dish, and let it stand till it is cold, and serve it up. Or a rich calf’s-foot jelly made clear and good, poured into the dish round the hedgehog; when it is cold, it looks pretty, and makes a neat dish; or it looks pretty in the middle of a table for supper . (Glass, 185)

For modern cooks, a half recipe should suffice and still allow you to serve an impressive, delicious and decorative dish to the table.I kept the full amount of custard since it is such a delicious addition to the hedgehog. My adaptation for modern cooks is as follows

‘Marzipan’ Base: 1 lb almonds 1/2 c. Sherry 1 T orange extract ¼ c. sugar (more if you like a sweeter confection) 3 whole eggs 3 egg yolks ¼ lb butter ½ pint cream Decorations: Slivered almonds Raisins Custard sauce: 1 pt. Cream 4 egg yolks ¼ c. brown sugar Blanch the almonds (Put raw, whole almonds in boiling water. Boil for 2 minutes. Drain and cool. Squeeze or rub the almonds to pop them out of their skins.) and crush them to paste, adding the sherry and orange extract gradually. Put the almond mixture and remaining base ingredients in a saucepan. Cook over medium heat until it is stiff enough to mold. Make into small oval shapes resembling hedgehogs- approximately ½ c. mixture for each one. Set each in a custard dish or plate with a lip. Add raisins for eyes, and slivered almonds for spines. To make the custard, Mix the cream, egg yolks, and brown sugar. Cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until thickened. Do not boil. Pour the warm custard into each dish with the hedgehogs. Serve warm or chill and serve cold.

Notes:

Hannah Glass’s recipe is obviously designed for a wealthy home, with a large kitchen staff. Pounding the almonds in a mortar is difficult and time consuming. Whole blanched almonds are as slippery as real hedgehogs, and are as likely to pop out of the mortar and go flying as they are to be crushed. I found chopping them first made it much easier. But crushing them is still time consuming. The modern cook can use a food processor to get the same effect. I ended up with a sort of crunchy paste, similar to crunchy peanut butter, but drier and finer. More pounding or processing may have made a smoother paste, but I was running out of time. For a smoother dish, the modern cook could purchase marzipan paste.

It is possible to get or make orange flower water (distilled from orange petals) but I substituted orange extract.

Canary is a sweet wine from the Canary Islands. I used sherry as a reasonable alternative.

Not surprisingly, hedgehogs continue to inspire. Pinterest boards abound with ideas for hedgehog crafts, cards, and cakes. In fact, I made a hedgehog cake for my daughter-in-law’s baby shower.

Though thoroughly modern in taste and ingredients, this hedgehog unwittingly carries on the medieval tradition of the subtlety. Food for show? Absolutely. We’re not so far from those lords and ladies of old trying to impress their guests. And who doesn’t like hedgehogs?

Even more than apple pie, the pumpkin is symbolic of early America. Before Europeans landed, Native Americans used pumpkins for both food and medicine. Indeed, early colonists from England found pumpkins so important that one of the earliest folk songs from the colonies satirizes the ubiquitous pumpkin in the oft-quoted pilgrim verse from c. 1630.

Even more than apple pie, the pumpkin is symbolic of early America. Before Europeans landed, Native Americans used pumpkins for both food and medicine. Indeed, early colonists from England found pumpkins so important that one of the earliest folk songs from the colonies satirizes the ubiquitous pumpkin in the oft-quoted pilgrim verse from c. 1630.

As fall gave way to winter this week, children all over the country dressed in funny, scary or highly marketed costumes, and went out begging for candy. With colorful decorations and ubiquitous advertising on all sides, it is easy to lose track of the main theme of this week, which is death.

As fall gave way to winter this week, children all over the country dressed in funny, scary or highly marketed costumes, and went out begging for candy. With colorful decorations and ubiquitous advertising on all sides, it is easy to lose track of the main theme of this week, which is death.

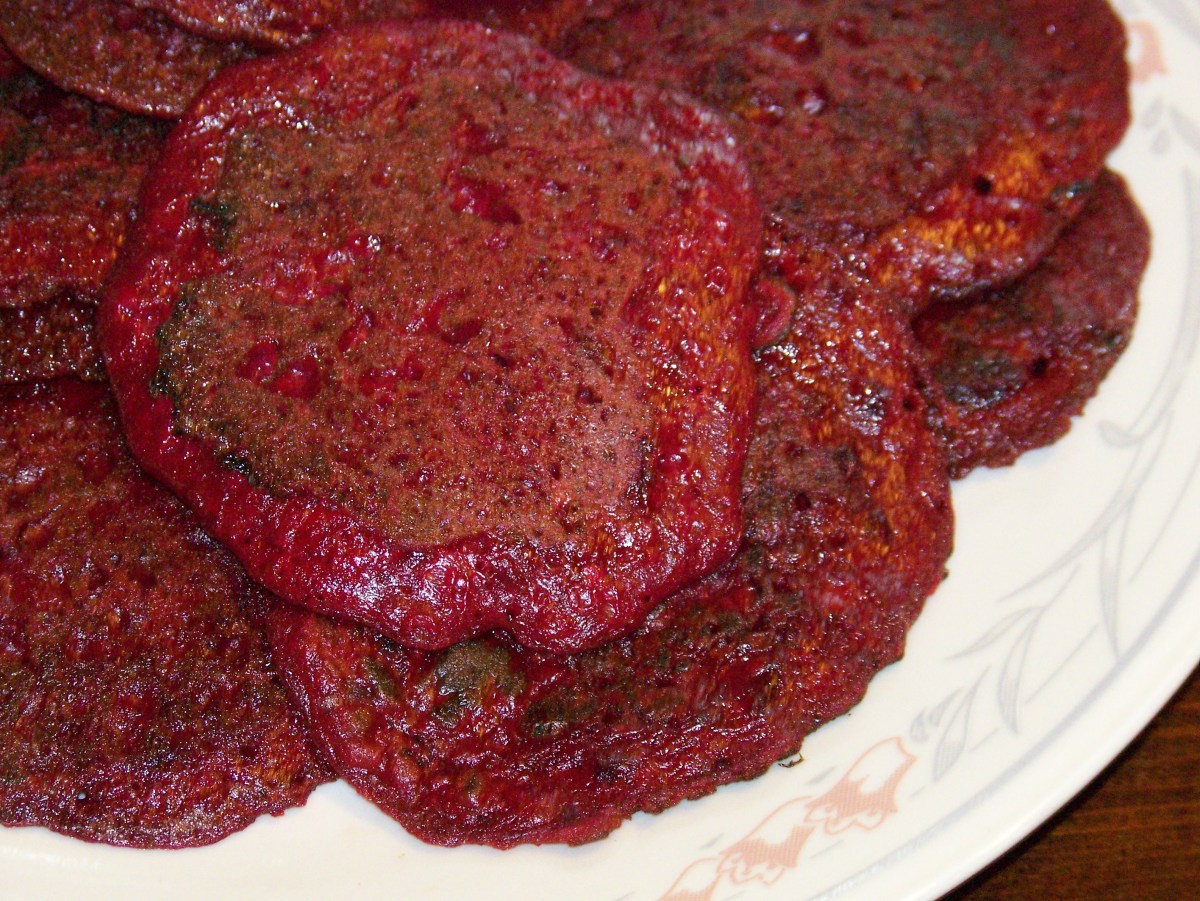

Beets are prettier than potatoes, more colorful than turnips and easier to pronounce than rutabagas. So why do so many of my friends and family say they hate beets? Some even say the lovely purple root tastes like dirt. (They are probably reacting to the high levels of geosmin in beets, which is the element that gives a garden a rich smell after a rain.

Beets are prettier than potatoes, more colorful than turnips and easier to pronounce than rutabagas. So why do so many of my friends and family say they hate beets? Some even say the lovely purple root tastes like dirt. (They are probably reacting to the high levels of geosmin in beets, which is the element that gives a garden a rich smell after a rain.

These days, beets turn up in salads, added to brownies or burgers or even in hummus. So many delicious ways to serve beets! What’s your favorite?

These days, beets turn up in salads, added to brownies or burgers or even in hummus. So many delicious ways to serve beets! What’s your favorite?