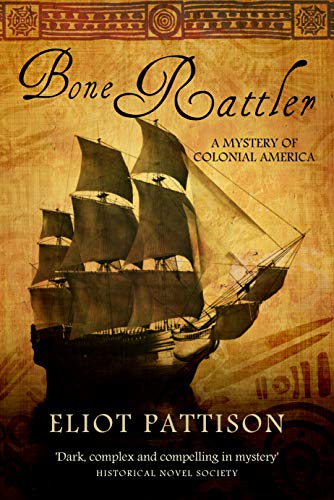

A Mystery Novel of Colonial America

by Eliot Paterson

Bone Rattler by Eliot Paterson is a disturbing book. It tears apart some of the cherished myths surrounding the take over of the Americas by Europeans. The book lays bare the greed and corruption of the eighteenth century settlers. In so doing, Patterson portrays the savagery on all sides of the French and Indian War, the oft forgotten precursor to Revolution.

The story follows Duncan McCallum, a Highland Scot, who lost his family in the bloody aftermath of Culloden. The story begins on a convict ship. Duncan has been sentenced to transportation and indenture in the New World. Indenture was a common occurrence in the 17th and 18th centuries, with individuals signing a contract to serve a pre-determined number of years in exchange for passage to the new world and a chance to start fresh. But self-imposed indenture was usually not nearly as harsh as the convict’s indenture. In addition, any indentured person could be sold into any kind of work. In fact, the indentured convict had no more rights or protections than an enslaved person. The primary difference, and it’s a big one, is that indenture was usually temporary.

Bone Rattler, at its core, is a murder mystery, keeping the reader guessing all the way through. For Duncan the murder and the mystery start aboard the ship when his friend is killed and Duncan saves the life of a mysterious woman. Duncan’s quest to find the murder and discover the identity of the woman lead him to a chilly discovery of the depravity ot some of the colonists.

Duncan is a product of his times and holds the same fears and prejudices toward the ‘savages’ as his countrymen do. But Duncan is himself a victim of British prejudice against the Scots, who were widely regarded as brutes and savages. Duncan is terrified of what awaits him in the wilderness of America, but he is open-minded enough to gradually recognize his folly in judgements, and to learn from his new surroundings.

What he learns astonishes him. Where he thought that the Indian captives were demoralized and suffering from the horrors they face while enslaved by the Inidans, unturned out to be complete wrong. Without given away the story, I can only say I found Duncan’s transformation both believable and satisfying.

At the beginning of the book, Duncan believes hope is the ‘deadliest thing in the world’ (1). But by the end, I find hope in the ability or at least the possibility of understanding the ‘other’. Many of the prejudices and misunderstandings that came which those early colonists remain today. Many modern Americans are still wary of strangers, ignorant of Native American beliefs, and willing to climb up on the backs of those less fortunate in order to grab more for themselves. The greed that crossed the ocean in the 17th and 18th century has not disappeared.

However, not all the colonists fit this mold, and not all people today do either. There are a good number of people both then and now reaching for understanding and justice. This book is worth reading, if only for the example Duncan provides that working toward a better world is not futile.

When it comes to legends of Irish princesses, don’t expect a happy ending. Their stories are decidedly tragic.

When it comes to legends of Irish princesses, don’t expect a happy ending. Their stories are decidedly tragic.

Earlier this summer I had the very distinct pleasure of attending the popular rap-musical, Hamilton, with my daughter in Chicago. A lot has been written about this show, and its well-deserved popularity. Indeed, the music, the lyrics, the acting, the set, the choreography–all that and more are truly amazing.

Earlier this summer I had the very distinct pleasure of attending the popular rap-musical, Hamilton, with my daughter in Chicago. A lot has been written about this show, and its well-deserved popularity. Indeed, the music, the lyrics, the acting, the set, the choreography–all that and more are truly amazing.