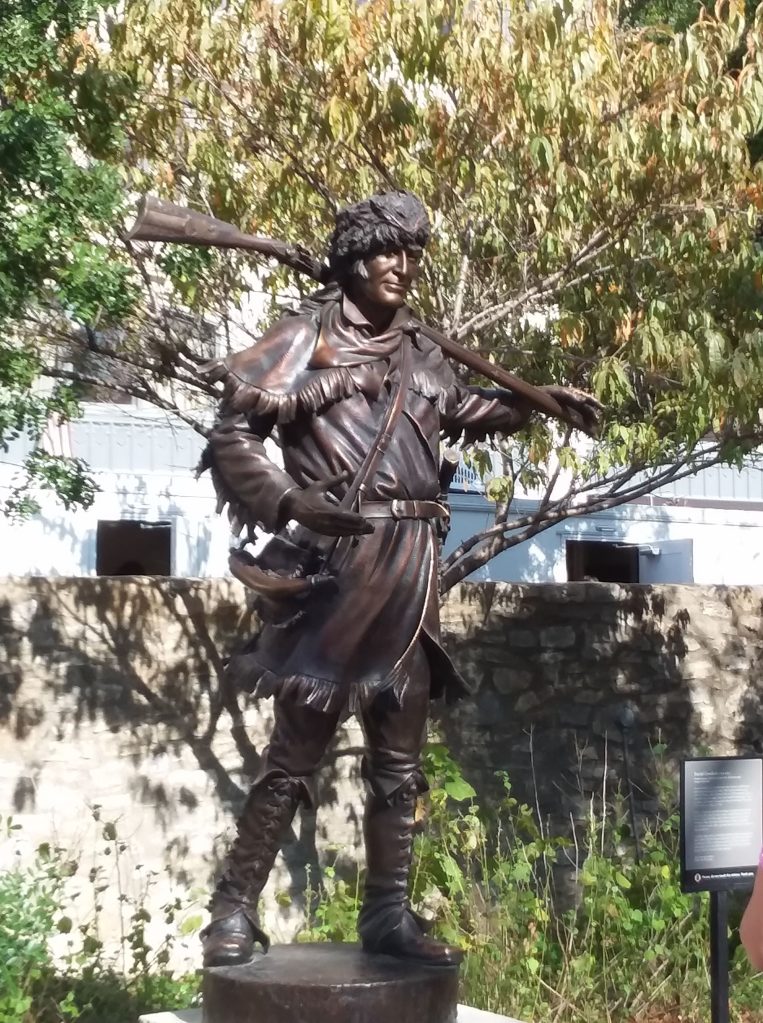

In elementary school, we all learn about the Lewis and Clark expedition, that epic journey of discovery. Most of us have also heard of Sacagawea, and her vital role in the expedition as translator, guide, and ambassador. Less well-known are the living conditions of the company. Since I’m especially interested in women’s contributions to history I find Sacagawea’s story fascinating, not just because of the important guidance she gave the captains, but also because of her skill as a mother.

Remember, Sacagawea was a Shoshoni girl about 10 years old when she was kidnapped by the Hidatsa. She was taken from her home in Idaho to a village near Mandan, North Dakota. There she was sold, along with another girl from her village, to a Frenchman, Toussaint Charbonneau. Charbonneau married both girls, though I have never heard whether or not the girls agreed to the wedding.

In any case, Sacagawea gave birth to their son, Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau (nicknamed Pompey), on February 11, 1805. Less than two months later, on April 5, 1805, the company departed for the west, with Sacagawea carrying her infant son.

Now I’d be the last to suggest that modern parenting is easy. All decisions regarding the health, safety, and future happiness of the child rest on the parent’s shoulders. But today we have disposable diapers, along with innumerable gadgets, equipment, toys, and carrying devices to make caring for an infant easier. Can you imagine setting off on a journey with your child on your back? There were no air-conditioned cars or motels along the way. Sacagawea travelled by foot, horse or open boat the entire journey, and she kept her baby alive.

In the winter of 1806, when Pompey was still less than one year old, the Lewis and Clark expedition reached the Pacific Ocean and built Fort Clatsop. They started building on December 8, 1805, and moved in on Christmas Eve, though the roof was not yet finished. Although Sacagawea had a vote in the decision of where to put the fort, I’m sure she never imagined the mud.

Days and days of mud.

I visited Fort Clatsop on a beautiful, warm and sunny day. The surrounding cedar forest was cool and shady, with a carpet of soft needles lining the paths. The Lewis and Clark expedition had a vastly different experience. Of their three month stay at this fort, it rained all but twelve days.

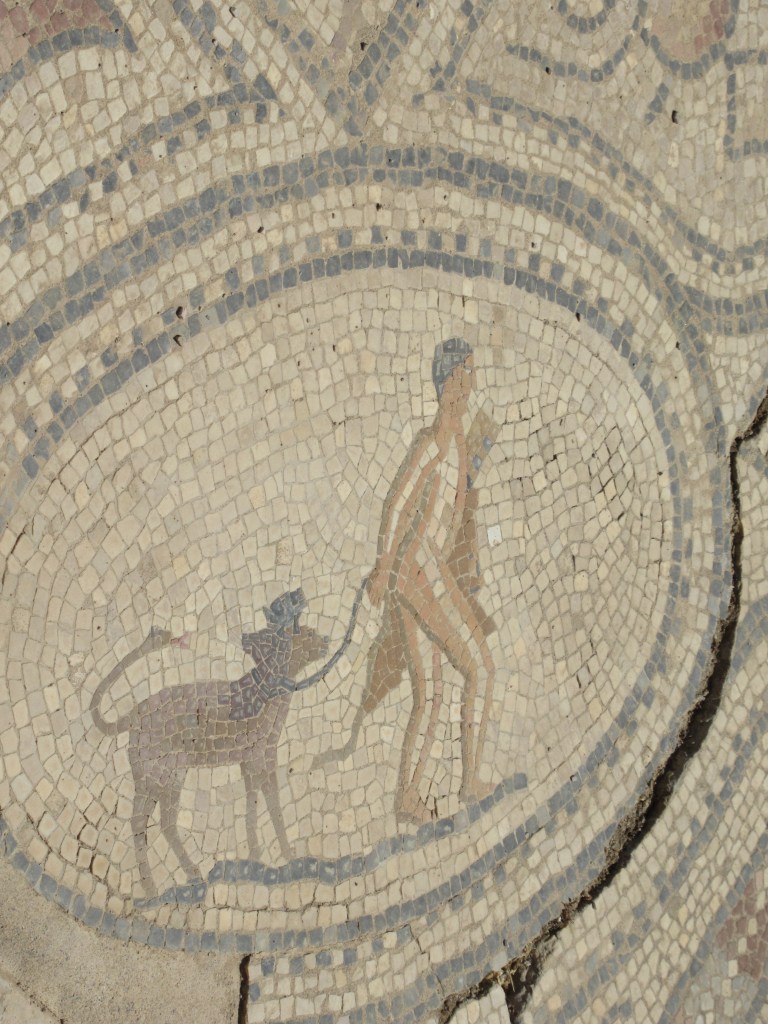

On top of the endless rain, the fort was built for military purposes, not comfort. Thirty two men, one woman, a baby, and a dog lived in the two buildings. The angled roofs were high on the outer edges, and sloped down to a central courtyard. That means all that rain collected in the narrow yard between the buildings. Inside was dark, smoky, and full of fleas. Outside was wet.

Here Pompy passed his first birthday. He probably crawled about in the mud and played with the men or the dog. He may have spoken his first words and learned to walk. And through it all, Sacagawea kept him healthy.

We learn from the journals Lewis and Clark kept that they left Fort Clatsop on March 23, 1806, as soon as they could. Everyone was tired of this miserable fort. I imagine Sacagawea was just as anxious as the men to leave. The journey back would be long and arduous, but never boring.

Perhaps having a roof over one’s head is not such a luxury where there’s a sea of mud beneath one’s feet.