Though the night when “visions of sugar plums danced” has passed, Christmas candy is still plentiful in my house. Christmas is a time of celebration, and celebration most often brings sweet treats. A little investigation shows that traditions of candy go way back.

Though the night when “visions of sugar plums danced” has passed, Christmas candy is still plentiful in my house. Christmas is a time of celebration, and celebration most often brings sweet treats. A little investigation shows that traditions of candy go way back.

It seems humans have always had a taste for sweet things. First honey, and later, sugar. Sugar from cane was first cultivated in India, and was kept as a closely guarded secret until Darius of Persia invaded in 510 BC and discovered the ‘reed that gives honey without bees’. Then in 642, Arabs invaded Persia and learned about sugar. As the Arab empire spread through Africa, the Middle East and Spain, so too did the growth and cultivation of sugar. Crusaders in the 11th century brought knowledge of sugar to Europe, where sugar was regarded as another exotic (and expensive) spice.

When Europeans invaded the New World, they discovered the climate in the Caribbean was very good for growing sugarcane. Even though there were over a hundred sugar refineries in Great Britain by 1750, sugar was still a luxury item partly because it was so highly taxed. (The Sugar Act of 1764 angered the Colonists so much that it was repealed in 1765, and contributed to the revolt against the Stamp Act of 1765.)

The earliest candies were comfits, which are seeds or nuts coated with layers of hardened sugar syrup. These first candies were medicines, prescribed by doctors or apothecaries to treat stomach troubles. (Perhaps this is why candy came to be associated with Christmas — after all, indigestion is common after a hearty Christmas dinner.)

Clement C. Moore’s famous poem strengthened the connection between Christmas and candy with his talk of sugarplums. I always thought sugar plums were candied or sugar-coated plums, but it turns out they aren’t plums at all. As early as 1608, a sugarplum was something sweet or agreeable in nature, not just something to eat. In the 17th through 19th century, sugarplums were small, flavored candies or comfits, (Some favorite fillings included cardamom, cinnamon, coriander, almonds, walnuts, and fennel.)

Making comfits was often the work of apothecaries since the layering process took time and skill, but colonial housewives made their share of sweet treats. One such treat is candied orange peel.

Like sugar, oranges originated in India, though oranges were known much earlier than sugar cane. By the 1st century, Chinese farmers were cultivating orange groves. Romans brought oranges to Europe around the same time. But these were all bitter oranges which are good for flavorings, marmalades, and perfumes. The sweet orange was brought by Portuguese traders from the Tamil Kingdom in India to Europe in the 16th century. They were quickly brought to the New World. As early as 1513. Ponce De Leon planted orange trees in Florida to help prevent scurvy among the sailors. In today’s world, oranges are one of the most popular fruits, second only to apples. However, in the 18th century, oranges had to be imported from the West Indies and so, like sugar, they were a luxury for most American colonists.

Many of the cookery books from the 18th century contain recipes for preserving fruit. One very popular way was candying, or boiling the fruit in a sugar syrup. In that way fruit could be enjoyed even in the winter when it was no longer in season.

John Townshend’s The Universal Cook Or Lady’s Complete Assistant (printed in London, 1773) has a fairly simple recipe for candied orange peels.

Having steep;d your orange peels as often as you shall judge convenient, in water, to take away the bitterness; then let them be gently dry’d and candy’d with syrup made of sugar. (261)

Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery and Booke of Sweetmeats is older, with more erratic spelling. This manuscript hand-written in the 17th century and was in Martha Washington’s possession from 1749- 1799, and was transcribed and annotated by Karen Hess in 1981. This recipe provides a bit more direction.

To Candy Orring Pills

Take Civill orringes & pare them very thin, then cut them in little pieces, & lay them in faire water a day & a night, & shift them evening and morning, then boyle them, & shift them when the water is bitter into another water, & continew this till the water & boyling hath made them soft & yt theyr bitterness be gon. Then dreyne ye water from them, & make a thin sirrup, in which boyle them a pritty while. Then take them out & make another sirrup a little stronger, and boyle them a while int yt. then dreyne ye sirrup from them, & boyle another sirrup to candy height, in wch put them. Then take them out & lay them on plats on by one. When they are dry, turne them & then they are done. (284)

(Note: All of the early recipes I found for candying oranges used bitter (Seville) oranges. Since modern cooks mostly have sweet oranges, it is not necessary to boil the peels in as many water baths to remove the bitterness.)

A modern cook can use the simpler method for candying orange peels:

- 1 ½ c water

- 1 ⅓ c sugar

- 3 oranges

Score each orange in quarters, and remove the peel. Slice the peels ⅛ to ¼ inch wide.Bring to a boil and simmer these in clear water 10- 15 minutes. Drain and rinse. Mix water, sugar and the boiled orange peels. Simmer for 40-45 minutes, until the water is nearly gone, but before the sugar turns to hard crack stage.

Lay the peels on a flat surface to cool and dry before eating.

I can’t guarantee that candied orange peels will aid digestion, but they surely are a sweet treat for the New Year.

Sources:

Hess, Karen (transcriber and anotater). Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Rupp, Rebecca. “What are Sugar Plums Anyway?” The Plate. National Geographic. December 23, 2014. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/people-and-culture/food/the-plate/2014/12/23/visions-of-sugarplums/

Townshend, John. The Universal Cook Or Lady’s Complete Assistant . London: S. Bladon, 1773)

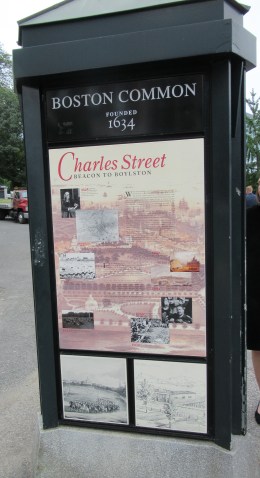

On a crisp fall day in 2018, Boston Common plays host to all sorts of people. Though the sky is overcast, tourists stroll along the winding paths pst the Frog Pond, Children play . and old men park on benches to read the newspaper. Along the north side of the park a musician strums his guitar, the open case in front of him inviting donations. In another corner, several dozen people gather for an ecumenical outdoor church service led by a woman with a microphone. In short, the oldest public park in America is the heart of Boston, providing a free, open, space for the people to use as they will, just as it has done for the last 384 years.

On a crisp fall day in 2018, Boston Common plays host to all sorts of people. Though the sky is overcast, tourists stroll along the winding paths pst the Frog Pond, Children play . and old men park on benches to read the newspaper. Along the north side of the park a musician strums his guitar, the open case in front of him inviting donations. In another corner, several dozen people gather for an ecumenical outdoor church service led by a woman with a microphone. In short, the oldest public park in America is the heart of Boston, providing a free, open, space for the people to use as they will, just as it has done for the last 384 years.

Ask a dozen people about mincemeat and you’ll like get one of two answers. Some will fondly remember how their mother or grandmother made mincemeat pies. Most of the rest will say, “Huh? What’s in that anyway? Does it really have meat in it?”

Ask a dozen people about mincemeat and you’ll like get one of two answers. Some will fondly remember how their mother or grandmother made mincemeat pies. Most of the rest will say, “Huh? What’s in that anyway? Does it really have meat in it?”

September is the harvest month–the time to gather the abundant bounty from our summer gardens . And nothing demonstrates abundance quite so well as zucchini squash. It’s so easy to grow that even a complete amateur gardener can produce more zucchini than any family can reasonably eat in one season. Zucchini grows well in almost any soil, survives drought and neglect and even produces when choked by weeds left by the lazy gardener. But zucchini is a relative newcomer to the panoply of summer squashes. It is a hybrid variety of Cucurbita pepo (all summer squashes belong to this family), developed in Italy in the second half of the 19th century. The first records of zucchini in America are not quite a hundred years old, dating from the 1920’s.

September is the harvest month–the time to gather the abundant bounty from our summer gardens . And nothing demonstrates abundance quite so well as zucchini squash. It’s so easy to grow that even a complete amateur gardener can produce more zucchini than any family can reasonably eat in one season. Zucchini grows well in almost any soil, survives drought and neglect and even produces when choked by weeds left by the lazy gardener. But zucchini is a relative newcomer to the panoply of summer squashes. It is a hybrid variety of Cucurbita pepo (all summer squashes belong to this family), developed in Italy in the second half of the 19th century. The first records of zucchini in America are not quite a hundred years old, dating from the 1920’s. This original recipe calls for peeling the pattypan squash. I found that it is very difficult to peel because of the irregular shape. In the days of modern appliances, peeling the squash is unnecessary. Placing the boiled, unpeeled squash in a food processor and processing it for 2 minutes produces a sauce just as smooth as the colonial method of forcing the cooked squash through a colander.

This original recipe calls for peeling the pattypan squash. I found that it is very difficult to peel because of the irregular shape. In the days of modern appliances, peeling the squash is unnecessary. Placing the boiled, unpeeled squash in a food processor and processing it for 2 minutes produces a sauce just as smooth as the colonial method of forcing the cooked squash through a colander.

Earlier this summer I had the very distinct pleasure of attending the popular rap-musical, Hamilton, with my daughter in Chicago. A lot has been written about this show, and its well-deserved popularity. Indeed, the music, the lyrics, the acting, the set, the choreography–all that and more are truly amazing.

Earlier this summer I had the very distinct pleasure of attending the popular rap-musical, Hamilton, with my daughter in Chicago. A lot has been written about this show, and its well-deserved popularity. Indeed, the music, the lyrics, the acting, the set, the choreography–all that and more are truly amazing.