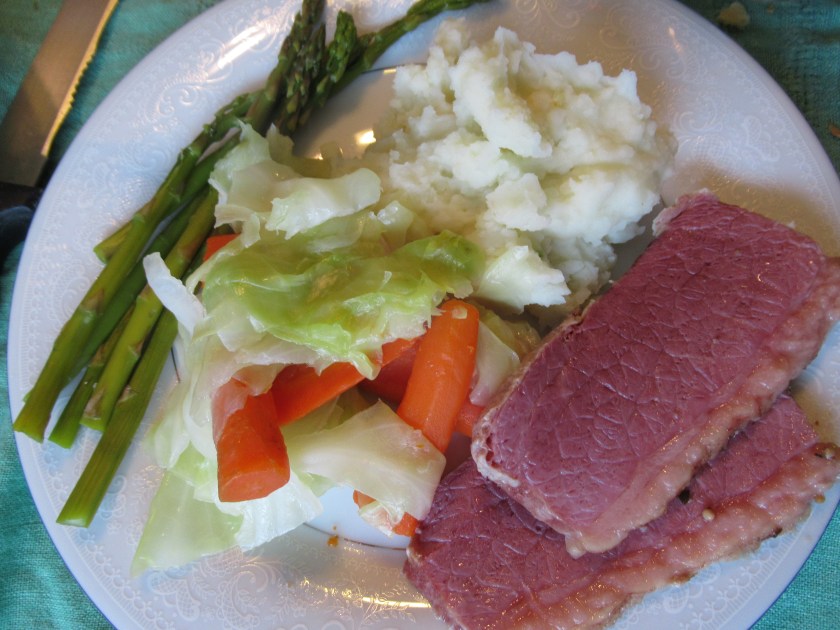

As March draws toward its closing, we have just finished celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the biggest Irish-American holiday of the year, with one of my favorite meals–traditional corned beef and cabbage.

As March draws toward its closing, we have just finished celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the biggest Irish-American holiday of the year, with one of my favorite meals–traditional corned beef and cabbage.

Except that it’s not.

Not traditional Irish that is. In Ireland, corned beef is not particularly special or common. So how did this iconic dish gain first class status for Irish-Americans? The story is complicated.

First of all, what is corned beef and how did it get its name? Corned beef is beef preserved with a salt brine,various spices, and saltpetre.The saltpetre gives the meat its pinkish color. (Modern corned beef uses sodium nitrite.) ‘Corn’ related to kernel, means grain and refers to the large grains of salt used in the process.

The Irish did not invent corned beef. Many cultures around the world salted beef or other foods as a way of preserving them even before the Greeks and Romans. Corned beef appears in Irish cookery as early as the 12th century. The dish is mentioned in a satiric poem, Aislinge Meic Conglinne, about a king trying to defeat gluttony. It’s interesting, because in ancient and medieval Ireland, only kings were wealthy enough to eat beef. Cattle were a mark of wealth and status. Though used for dairy products, cows were not often eaten. Most of the Irish people ate pork, salted or fresh.

Then things changed in the 12th century, when England invaded Ireland. By the 16th century, England ruled all of Ireland. The English brought their love of beef (inherited from the Romans during that invasion centuries earlier). Ireland had wonderful pasture lands for raising beef cattle. In fact, the English overlords did such a good job of expanding beef production that in the 1660’s, the English parliament passed the Cattle Acts which prohibited exporting Irish beef since the Irish beef was hurting English farmers.

At the same time that Ireland was increasing beef production, the English navy was expanding, and English merchants (including slavers) began increased trade with the new world. Salted beef was very important for long sea voyages because it keeps well. Another factor in the rise of Irish corned beef was the tax on salt. Ireland had a much lower tax on salt imported from Spain or Portugal.

This plentiful combination of good salt and good beef meant that the Irish became known for great exported corned beef. They even sold it to both sides (French and English) during the Seven Years War. However, since corned beef was now an important trade commodity, it was too expensive for the average Irish to eat.

In another twist to the story, the demand of corned beef indirectly contributed to the Great Potato Famine in the middle of the 19th century. So much acreage was used for pasture land for beef production for export that ⅖ of the total population of Ireland relied completely on potatoes. When the blight hit the potato crop, they had nothing else to eat.

Thousands of starving Irish came to America, where they found corned beef regarded as poor food, fit mostly for slaves. For the first time, corned beef was affordable and the Irish immigrants embraced it. And so began the association of corned beef and and cabbage (another cheap food) with the celebration of all things Irish.

Most people buy packaged corned beef from the supermarket, but I found a couple of recipes from colonial times for salting your own beef.

The one I tried comes from The American Frugal Housewife, by Mrs. Child, (12th Edition) published in 1832.

It is good economy to salt your beef as well as pork. Six pound of coarse salt, eight ounce of brown sugar, a pint of molasses, and eight ounces of salt-petre are enough to boil in four gallons of water. Skim it clean while boiling. Put it to the beef cold; have enough to cover it’ and be careful your beef never floats on the top. It it does not smell perfectly sweet, thurw in more slat. If a scum rises upon it, scald and skim it again, and pour it on the beef when cold. …A six pound piece of corned beef should boil full three hours. (41-42)

Mrs. Child does not say how long to leave it in the brine, before boiling, but she does say that in summer the beef won’t keep well more than a day and a half, but will be good for a fortnight in winter. She also recommends leaving out the saltpetre in summer since it inhibits the absorption of other salts, and so the meat won’t keep as long.

For my recipe, I left out the saltpetre (because I didn’t have any) and adjusted for a much smaller piece of beef.

Corned /Salted Beef

1 c. coarse salt

¼ c. brown sugar

¼ c. molasses

2 qts. water

2 lb. piece of beef (rump roast is all right, but a fattier cut works better)

First, make the brine. Pu all ingredients except the beef in a large pot. Bring it to a boil and boil until the salt and sugar dissolves. Skim it if necessary, then cool it thoroughly. Put the beef and brine in a non-reactive container. Make sure the brine can cover the beef. The beef will float, so put a weight (like a plate or inverted bowl) on the beef to hold it down in the brine. Refrigerate for 3 days,

turning the beef daily.

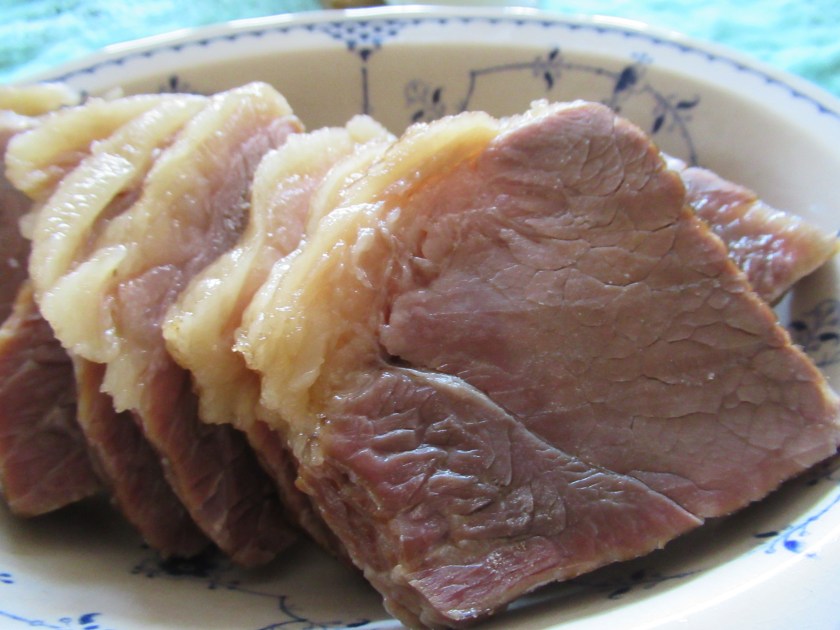

To cook the beef, drain the brine, rinse the meat, and put it in

fresh water. Boil it for about 2 hours.

Since this recipe does not include the spices of the more common corned beef, the result tastes like nicely salted roast beef- quite delicious. Other colonial recipes suggest adding various spices when boiling the beef, but I didn’t have a chance to try those. Perhaps next year.

In the meantime, I’ll keep my Irish (American) tradition. Erin go bragh (Éirinn go Brách)!

‘Marzipan’ Base:

‘Marzipan’ Base:

On a bleak winter’s day in January, nothing beats curling up with a cup of hot tea and a good book. Snow Falling on Cedars, by David Guterson, is a perfect choice for metaphorically shivering in your cozy chair.

On a bleak winter’s day in January, nothing beats curling up with a cup of hot tea and a good book. Snow Falling on Cedars, by David Guterson, is a perfect choice for metaphorically shivering in your cozy chair. Part 2: Train wrecks

Part 2: Train wrecks

The Holiday Train

The Holiday Train

Even more than apple pie, the pumpkin is symbolic of early America. Before Europeans landed, Native Americans used pumpkins for both food and medicine. Indeed, early colonists from England found pumpkins so important that one of the earliest folk songs from the colonies satirizes the ubiquitous pumpkin in the oft-quoted pilgrim verse from c. 1630.

Even more than apple pie, the pumpkin is symbolic of early America. Before Europeans landed, Native Americans used pumpkins for both food and medicine. Indeed, early colonists from England found pumpkins so important that one of the earliest folk songs from the colonies satirizes the ubiquitous pumpkin in the oft-quoted pilgrim verse from c. 1630.

One of the best gifts is a good book. The trouble is, picking a book for a fellow reader can be tough. It’s hard enough to keep track of what I’ve read, let alone remembering what my sisters, my children and my friends have on their shelves. One option is to buy new, just-published works. That’s a great idea, but if I take time to read the new book to make sure it is what the recipient would like, it’s not new any more.

One of the best gifts is a good book. The trouble is, picking a book for a fellow reader can be tough. It’s hard enough to keep track of what I’ve read, let alone remembering what my sisters, my children and my friends have on their shelves. One option is to buy new, just-published works. That’s a great idea, but if I take time to read the new book to make sure it is what the recipient would like, it’s not new any more.