Spring is finally here. The ice is off the lake and the trees are budding out. With the end of the sugaring season, it’s time to talk about maple sap. Maple syrup is one of the uniquely American foods. No one knows for sure when the indigenous people of North America began collecting ‘sweet water’ from maples and other native trees, but it was long before Europeans arrived. Sixteenth century French fur traders described how the natives collected sap in birch-bark baskets. When the sap rose in late winter and other food sources were scarce, Indians drank the ‘sweet water’ straight. They also boiled meat or other foods in it. Using hot rocks they boiled it down to make syrup or sugar.They even molded the sugar into decorative shapes. In other words, maple sap was an important part of the native food culture in North America.

Spring is finally here. The ice is off the lake and the trees are budding out. With the end of the sugaring season, it’s time to talk about maple sap. Maple syrup is one of the uniquely American foods. No one knows for sure when the indigenous people of North America began collecting ‘sweet water’ from maples and other native trees, but it was long before Europeans arrived. Sixteenth century French fur traders described how the natives collected sap in birch-bark baskets. When the sap rose in late winter and other food sources were scarce, Indians drank the ‘sweet water’ straight. They also boiled meat or other foods in it. Using hot rocks they boiled it down to make syrup or sugar.They even molded the sugar into decorative shapes. In other words, maple sap was an important part of the native food culture in North America.

While maple trees grow in Europe, Europeans did not discover the process. One explanation for this has to do with climate. Sap rises in trees in late winter as the temperatures vary between daytime highs of 40 degrees and lows of 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Without this fluctuation of temperature, the sap does not recede and flow. Most of the areas in Europe where maples flourish do not have the right temperature fluctuation.

Interesting, but what does this have to do with slavery? The answer is both complicated and fascinating.

In Colonial and Early America, one of the most important imports was cane sugar produced in the West Indies by slave labor. After the United States won independence from British rule, the new nation looked for other ways to assert their self-sufficiency. Maple sugar, produced at home, was cheaper than imported cane sugar, and more patriotic.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, a prominent physician in Philadelphia, spoke out in favor of maple sugar. As an abolitionist, he hated supporting slavery through the use of cane sugar. He argued that maple sugar was both more pure in flavor and morally superior to cane sugar. In 1791, he wrote to Thomas Jefferson, “I cannot help contemplating a sugar maple tree with a species of affection and even veneration, for I have persuaded myself, to behold in it the happy means of rendering the commerce and slavery of our African brethren in the sugar islands as unnecessary, as it has always been inhumane and unjust.”1 Other patriotic abolitionists also urged citizens to “Make your own sugar, and send not to the Indies for it. Feast not on the toil, pain and misery of the wretched,” 2.

For a time, the scheme to promote maple sugar worked. Frugal farmers found that tapping maple trees was cheaper than buying expensive cane sugar. Abolitionists rallied to support the cause. Thomas Jefferson, who hated slavery though he never figured out how to free his own slaves, joined in the effort. He became a member of the Society for Promoting the Manufacture of Sugar from the Sugar Maple Tree, and urged farmers to plant maples and develop a large enough business to export the sugar. In this way, the Caribbean stronghold on the sugar market would be broken, and slave labor would no longer be needed. Jefferson even tried growing maple trees at Monticello, though without success.

Maple sugar became a symbol of freedom well into the 19th century. The Vermont Almanac in 1844 urged readers “suffer not your cup to be sweetened by the blood of slaves.”3

In spite of all these efforts, maple sugar as a commodity never became more economical than cane sugar. All of the schemes to promote maple sugar failed commercially, although production in the northeast did increase. Cane sugar continued to outsell maple sugar, and slavery continued until the Civil War.

One reason for the failure of the scheme is that maple sugar production is not as easy as Rush and Jefferson suggested. Although it doesn’t require slave labor, it does require a lot of sap and fuel to make. I collected 21 gallons of sap from my maple this year, and made 6 pints of syrup from it– a thinner, less viscous syrup than found in the store.

The process is fairly straightforward. Drill a hole or holes in the tree, collect the dripping sap in buckets. Strain and boil the sap down until it is the consistency of syrup. It took me about two weeks to collect the sap, and about 17 hours to boil it down.

Hannah Glasse gives similar directions for making maple sugar. She claims ”This sugar if refined by the usual process, may be made into as good single or double refined loaves, as were ever made from the sugar obtained from the juice of the West India cane” (Glasse, 141). She also talks about maple molasses, which is really what we would call maple syrup today.

Hannah Glasse gives similar directions for making maple sugar. She claims ”This sugar if refined by the usual process, may be made into as good single or double refined loaves, as were ever made from the sugar obtained from the juice of the West India cane” (Glasse, 141). She also talks about maple molasses, which is really what we would call maple syrup today.

A few pages earlier Hannah Glasse gives directions for mush, made with Indian meal (now called corn meal). She serves the mush with milk or molasses. Surely she meant maple molasses. The scheme for maple sugar to end slavery failed, but the push to use maple had sweet results.

To Make Mush

To Make Mush

Boil a pot of water, according to the quantity you wish to make, and then stir in the meal till it becomes quick thick, stirrintall the time to keep out the lumps, season with salt and eat it with milk or molasses. (Glasse, 137)

Modern version

- 3 c. boiling water

- 1 c. cold water

- 1 c. cornmeal1 t. Salt

- Maple syrup to taste

Add the salt to the boiling water. Mix the cornmeal with the cold water. Stir the mixture into the boiling water. Boil 5 minutes, stirring constantly. (Be careful as the boiling mush tends to spit hot bits out as you stir.) When it is thick enough, take it off the heat and let sit a few minutes. Serve with maple syrup.

1. Rush, Benjamin. An account of the Sugar-Maple Tree, of the United States, and of the methods of obtaining sugar from it, together with observations upon the advantages both public and private of this sugar (Philadelphia, 1792).

2 Farmer’s Almanac, 1803

3 Vermont Almanac 1844

4 Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. Cotton and Stewart. 1805.

Outside the sprawling city of Dubai lies the rest of the emirate- mostly sweeping sand dunes and scrubland. A few farms (date and camel) and villages dot the landscape. Sparse grasses grow in marginal areas and the occasional acacia or ghaf tree can be found, but for the most part the area is empty desert. About 134 miles east of the city of Dubai lies the ancient village of Hatta in the Hajar mountains. Hatta is unusual in that it is an enclave. That means that although it is part of the emirate of Dubai, it is surrounded by other political entities. The country of Oman curls around to the east and south, while the emirate of Ras al-Khaimah lies to the north, and the emirate of Ajman forms Hatta’s western border.

Outside the sprawling city of Dubai lies the rest of the emirate- mostly sweeping sand dunes and scrubland. A few farms (date and camel) and villages dot the landscape. Sparse grasses grow in marginal areas and the occasional acacia or ghaf tree can be found, but for the most part the area is empty desert. About 134 miles east of the city of Dubai lies the ancient village of Hatta in the Hajar mountains. Hatta is unusual in that it is an enclave. That means that although it is part of the emirate of Dubai, it is surrounded by other political entities. The country of Oman curls around to the east and south, while the emirate of Ras al-Khaimah lies to the north, and the emirate of Ajman forms Hatta’s western border.

As I scrambled up the steep, rocky path to the watchtower, I thought about why such a defensive tower was needed in such a remote place. Were they looking out for raiding tribesmen? Or perhaps, hoping for a desert caravan seeking a watering hole before reaching the Gulf of Oman? From the hilltop at the base of the tower, it’s easy to see why Hatta was important. Water is available here, a scarce commodity in such a barren part of the world. For now, the village is quiet and peaceful, Still, though the watchtowers are deserted, they remain standing, a stark reminder that the history of humanity is a story of conflict, even in the most remote places.

As I scrambled up the steep, rocky path to the watchtower, I thought about why such a defensive tower was needed in such a remote place. Were they looking out for raiding tribesmen? Or perhaps, hoping for a desert caravan seeking a watering hole before reaching the Gulf of Oman? From the hilltop at the base of the tower, it’s easy to see why Hatta was important. Water is available here, a scarce commodity in such a barren part of the world. For now, the village is quiet and peaceful, Still, though the watchtowers are deserted, they remain standing, a stark reminder that the history of humanity is a story of conflict, even in the most remote places. To be honest, I would never have gone to Dubai if our daughter hadn’t moved there with her family. And I would have missed a gem.

To be honest, I would never have gone to Dubai if our daughter hadn’t moved there with her family. And I would have missed a gem.

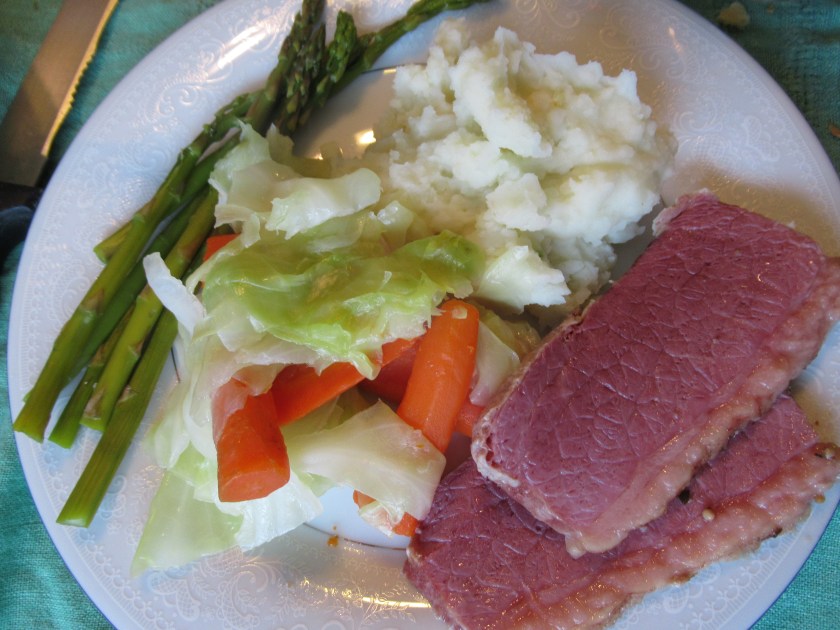

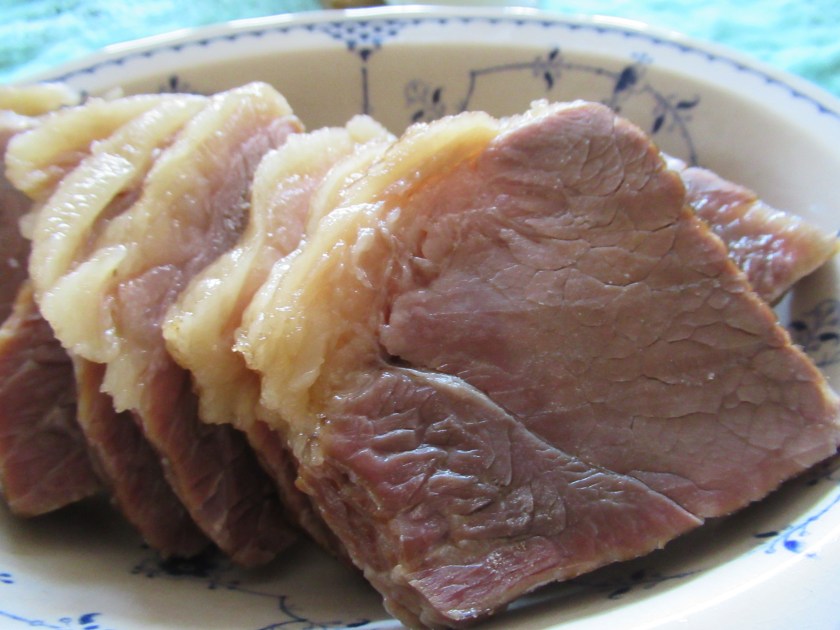

As March draws toward its closing, we have just finished celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the biggest Irish-American holiday of the year, with one of my favorite meals–traditional corned beef and cabbage.

As March draws toward its closing, we have just finished celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, the biggest Irish-American holiday of the year, with one of my favorite meals–traditional corned beef and cabbage.

‘Marzipan’ Base:

‘Marzipan’ Base:

On a bleak winter’s day in January, nothing beats curling up with a cup of hot tea and a good book. Snow Falling on Cedars, by David Guterson, is a perfect choice for metaphorically shivering in your cozy chair.

On a bleak winter’s day in January, nothing beats curling up with a cup of hot tea and a good book. Snow Falling on Cedars, by David Guterson, is a perfect choice for metaphorically shivering in your cozy chair. Part 2: Train wrecks

Part 2: Train wrecks

The Holiday Train

The Holiday Train