Chocolate is good for you! While many people make that claim tongue-in-cheek, there are actually a good many ways chocolate actually is a healthy choice, in moderation. (Unfortunately, no one claims the sugar and cream often mixed with chocolate are healthy.) Our ancestors also appreciated the healthful benefits of chocolate.

A little research into chocolate consumption turned up some surprising things. Most surprising, perhaps, is that chocolate was much cheaper in colonial America than it was in Europe at the same time. Though not as cheap as coffee, chocolate was a great deal cheaper than tea. One reason for this is the issue of transportation. Chocolate comes from cocoa beans (sometimes called cocoa nuts) which are indigineous to the Americas. It was easier and less expensive to acquire cocoa in New England, than it was to get the beans to Europe. Besides the shorter distance, it was easier to circumvent taxes and restrictive shipping laws. It’s likely that smugglers transported chocolate made in the colonies to Europe. While the cost of chocolate was too much for the common laborer or slave to indulge, any of the ‘middling sort’ could afford to buy chocolate.

Throughout the 18th century, chocolate makers thrived in the northern colonies where the weather made it possible to grind chocolate without it melting. One reason for the success of this cottage industry was that there were far fewer barriers for colonial entrepreneurs than for those in Europe. There were no guilds or monopolies restricting millers. A chocolate mill could be a small, foot-powered operation or a much larger water-powered manufacturer, or something in between powered by one or more horses. Millers could diversify, milled oats, coffee, spices, mustard or even tobacco at the same time, so that they didn’t have to rely on the supply of just one product. Each manufacturer had a unique recipe, making spiced or unspiced chocolate bars. Colonial Americans bought their chocolate based on who made it and where the beans came from, with a strong preference for locally made chocolate. Local chocolate was less likely to be adulterated or to have soaked up the smells and tastes of products transported beside the chocolate.

The second surprising fact I learned is how important chocolate was to colonial men and women. While we’ve all heard stories of the importance of tea, less attention has been given to chocolate. Many religious groups approved of chocolate because it was stimulating without being alcoholic. It was thought of as wholesome, nourishing, and medicinal. At least one religious leader in 1707 doled out chocolate bars and sermons to the sick of his parish. Colonial Americans appreciated the energizing effects of chocolate, while much of Europe though chocolate was a sign of decadence.

From the time of the Aztecs to WWII, soldiers have carried chocolate as a lightweight and satisfying food. During the French and Indian War, both the French troops and the British troops, and even some of the various Indian allies, counted on chocolate provisions. Ben Franklin organized shipments of chocolate to General Braddock’s troops, and a few decades later, during the Revolution, chocolate was considered a ‘necessity’ for American prisoners, and was included in the provisions sent to the Continental Army.

My third surprise was the many different ways chocolate was prepared during the 18th century. While it is uncertain exactly how the various groups of soldiers consumed their chocolate rations, recipes for common use abound. As we have seen before (see ‘Tis the Season for more chocolate history) chocolate was frequently a beverage. As such it was most popular as a nutritious and stimulating breakfast drink. Chocolate shells, or the husk of the cocoa bean after it has been roasted, were also steeped to make a sort of ‘tea’ that tastes like chocolate. This was apparently a favorite drink of Martha Washington. Finally, chocolate was grated to make cakes, cookies, and candies. A recipe for chocolate almonds (chocolate candies shaped like almonds) dating from 1705 calls for scraped chocolate, sugar, gum tragacanth, and orange water. Other contemporary recipes include almonds or rose water.

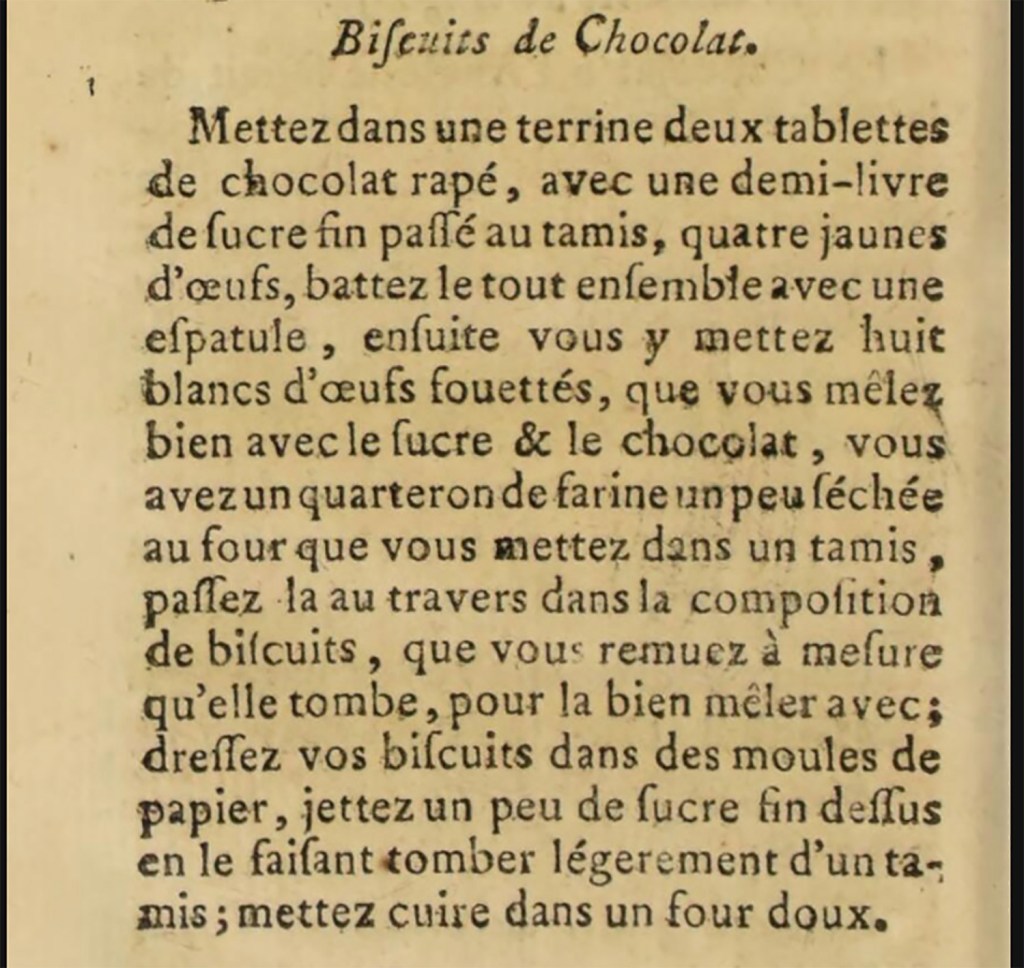

The recipe included here is for chocolate biscuits. Don’t be put off by the name. In this context, biscuit (deriving from the French for ‘twice baked’) follows the British and Irish usage: a biscuit is a type of cookie.

My translation of the recipe is as follows: (Note, I have added periods for clarity. The French author connected all of the sentences with commas only.)

BISCUITS OF CHOCOLATE. Put two tablets of grated chocolate in a bowl, with a half pound of sifted sugar, four egg yolks. Beat it all together with a spatula. Then put in eight egg whites beaten stiff and mix them well with the chocolate and sugar. Take a handful* of flour that has been dried in the oven, and sift it over the biscuit batter, stirring as it falls in order to mix it in well. Put your biscuits in paper molds. Sift a little fine sugar on top. Cook in a soft oven.

There are few difficulties with this recipe. The recipe writer kindly specifies the amount of eggs and sugar, but is less clear on the quantities of chocolate and flour. However, in pages preceding the recipe, the writer explains how to process chocolate into tablets that are one ounce each, so I can assume two tablets means two ounces. So the only problem with quantities is the amount of flour. A quateron can mean a quarter (of something, perhaps a quarter of a pound) or a handful. A quarter of a pound of flour is nearly 1 cup, which is much more than a handful. I opted for just enough flour to help the biscuits keep their shape. I made half of the original recipe for about 2 dozen cookies.

Finally since chocolate was sold both spiced and unspiced in the 18th century, I added cinnamon and pepper to the mix to replicate a simple spiced chocolate. The result was a delicious cookie with good chocolate flavor. For a crisp cookie, similar to a meringue, let the cookies cool, and keep in a very dry place. For a softer cookie, more like a sponge cake, bake for a shorter time and store in a sealed container to keep the moisture in.

Chocolate Biscuit Recipe 2 ounces chocolate (unsweetened baking chocolate) 1/2 c. sugar 1 t. Cinnamon ¼ t. Black pepper 2 eggs yolks 4 egg whites 1/3 c. flour Grate the chocolate. Mix with sugar, cinnamon and pepper. Add the egg yolks and stir well. In a separate bowl, beat the egg whites until stiff. Fold into the chocolate mixture. Gently add the flour. Drop by spoonfuls onto parchment paper (for a flat drop cookie) or fill paper muffin cups ¼ to ⅓ full. Bake at 325 for about 20- 25 minutes. (The time will vary based on how thick your cookies are and how crisp you like them.) The cinnamon and pepper add a nice, subtle ‘bite’ to the cookie. For a stronger, darker chocolate flavor, double the amount of grated chocolate.

Though chocolate has a reputation for decadence, this recipe offers more pleasure than guilt. After all, chocolate IS good for you.

Sources

Farmer, Dennis and Carol. The King’s Bread, 2d Rising: Cooking at Niagara 1726-1815. Old Fort Niagara Association, 1989. p.30.

Gay, James F. Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. Edited by Grivetti and Shapiro Copyright © 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 23: Chocolate Production and Uses in 17th and 18th Century North America , p. 294.

La science du maître d’hôtel, confiseur, à l’usage des officiers, avec des observations sur la connoissance & les propriétés des fruits. Suite du Maître d’hôtel cuisinier. (Anonymous). Paris. Par la compagnie de Libraires Associeés, 1778

These look simple and tasty. If I start baking again I’ll want to make them.

LikeLike